Seeds of Division

Conflict, dictatorships, instability and religious extremism in the Middle East, in the Horn of Africa, and in Central Africa plus the siren call of a better life has resulted in Europe’s worst immigration crisis since the Second World War. Hundreds of thousands of desperate people continue to crowd onto unseaworthy boats in hopes of crossing the Mediterranean, while thousands of Syrian refugees stream along railway tracks in the Balkans in hopes of finding asylum in Europe.

The number of dead continues to climb as overcrowded vessels flounder and sink, taking hundreds to a watery grave. More than 2500 people have drowned in the Mediterranean in the first nine months of this year. As in each of the ten years prior to 2015, the number of people who lose their lives in 2016 while looking for a better place to live will most likely surpass that. On the last week-end in August 2015, “the Italian coastguard plucked 4,400 people from the Mediterranean coast off Libya in 22 different operations…. Meanwhile the Greek coast guard picked up 877 people in 30 search and rescue operations.” (1)

In October 2014, the European Union suspended the Italian-run search and rescue operation known as Mare Nostrum. The decision was based on the belief that full-scale rescue operations would encourage more migrants to risk the sea journey from Libya to Europe. However, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), there was a four per cent increase in migrants while the service was stopped. The EU replaced Mare Nostrum with the smaller Triton border-control operation the following May. Non-governmental organisations spoke out against reducing the operation on the grounds that a smaller operation would have little hope of helping the growing number of people at risk. The IOM says that 27,800 people attempted to cross the Mediterranean in the first eight months of 2015. As life and death dramas play out in the Mediterranean, migrants from Syria, Eritrea, Sudan and Afghanistan continue to head north from Greece into Macedonia and Serbia, then on to Hungary in hopes of reaching such EU countries as Austria, Germany and Sweden.

In October 2014, the European Union suspended the Italian-run search and rescue operation known as Mare Nostrum. The decision was based on the belief that full-scale rescue operations would encourage more migrants to risk the sea journey from Libya to Europe. However, according to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), there was a four per cent increase in migrants while the service was stopped. The EU replaced Mare Nostrum with the smaller Triton border-control operation the following May. Non-governmental organisations spoke out against reducing the operation on the grounds that a smaller operation would have little hope of helping the growing number of people at risk. The IOM says that 27,800 people attempted to cross the Mediterranean in the first eight months of 2015. As life and death dramas play out in the Mediterranean, migrants from Syria, Eritrea, Sudan and Afghanistan continue to head north from Greece into Macedonia and Serbia, then on to Hungary in hopes of reaching such EU countries as Austria, Germany and Sweden.

EU Response insufficient

According to the European Foreign Council on Foreign Relations, EU states have fallen short in taking responsibility for what it calls a collective problem, calling its response to the crisis disjointed and insufficient.

France and Germany have called for an overhaul of laws governing asylum in the European Union on the grounds that some member countries have deliberately violated the law by refusing to take in migrants. After calling for migrants to be shared more evenly among EU states, Germany decided to no longer honour the Dublin Agreement, under which migrants are processed in the first country in which they set foot. After quietly suspending the deportation of asylum seekers who have crossed other countries to gain entrance to Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel publicly stated that she will accept thousands more refugees from Syria. Recently released government figures on those seeking asylum paint a picture that worries many Germans. “The government had assumed 450,000 would apply in Germany in 2015, more than twice the number last year. It now expects 800,000, almost four times last year’s total. In a space of weeks, the refugee crisis has thus pushed aside troubles in Greece and Ukraine as Germany’s biggest worry” (2)

Old Fault-lines Resurface

Across Europe, fear of Islamic terrorists blending in with the refugees is causing a backlash against immigrants. This was evident in the town of Heidenau near Dresden when an angry mob of several hundred protesters greeted buses loaded with 250 asylum seekers. Police spent three nights trying to allow the buses through and quell the mob, which threw bottles, stones, and fireworks at them while chanting Nazi slogans. (3)

The growth of such tragic migrations over the past ten years has led to a sense of hopelessness for many, a growing level of discomfort for leaders who are divided on what to do, and a backlash against immigration for others. This reaction is based on several reasons from xenophobia, fear of Islamic terrorism, to fear that the sheer number of migrants will overwhelm the established social order, leading to its collapse. However, fear is one thing and fact another. The 200-thousand migrants who have arrived so far this year make up 0.027 per cent of Europe’s total population of 740-million. That’s compared with Lebanon, which has a population of 4.5-million yet has accepted some 1.2-million Syrian refugees. (4)

Nation State or European Union

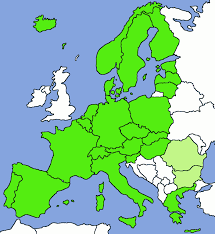

Under the Schengen Treaty, which went into effect in 1995, an area that now comprises 26 countries allows the free movement of goods and people across internal borders in Europe. A person can travel from anywhere in Scandinavia throughout Western and Central Europe to southern Europe without having to show a passport.  Bulgaria and Romania are legally bound to join the agreement, which would mean open borders between Central Europe and Greece. The only countries not set to join the Schengen Area are Albania, and the Balkan states of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Serbia, none of which are members of the European Union. However, given the divisions within Europe over how to deal with the dramatic influx of displaced migrants, leaders are faced with the dilemma of maintaining the Schengen Agreement without losing control of their rights in a sovereign nation.

Bulgaria and Romania are legally bound to join the agreement, which would mean open borders between Central Europe and Greece. The only countries not set to join the Schengen Area are Albania, and the Balkan states of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Macedonia, Kosovo, and Serbia, none of which are members of the European Union. However, given the divisions within Europe over how to deal with the dramatic influx of displaced migrants, leaders are faced with the dilemma of maintaining the Schengen Agreement without losing control of their rights in a sovereign nation.

Rights vs Borders

The emergence of nationalist right-wing parties who oppose immigration, and regional leftist movements in Europe reveals old fault lines based on identity and belonging. Groups in the former East Germany, having spent years under a communist regime, feel close to Ukraine and favour its integration into the EU. Right-wing groups want to maintain their identity as Germans. These fault lines are like phantom borders, and though they aren’t drawn on a map, they are becoming a politically powerful force. While a growing number of Europeans have voted in favour of slowing greater integration, efforts continue to expand the European Union to eventually include Ukraine, the Balkan states and Turkey. As the EU grows each time another external border is opened, internal border controls diminish under the Schengen Treaty.

Chancellor Merkel’s action to grant asylum to Syrian migrants is evidence of heart-felt humanity, or possibly a tendency to act quickly to resolve or at least minimise a problem. However, as head of a Nation State within the European Union and its legally porous internal borders, her decision has wider repercussions. Were Germany’s borders rigorously enforced through passport checks, her decision might be perceived as evidence of realism. The same could conceivably be argued on behalf of those leaders who abandoned the law to counter its intended purpose. Whether the decision maintains or restricts the right of asylum, ignoring a law that applies across all of Europe raises questions about rights versus borders.

Chancellor Merkel’s action to grant asylum to Syrian migrants is evidence of heart-felt humanity, or possibly a tendency to act quickly to resolve or at least minimise a problem. However, as head of a Nation State within the European Union and its legally porous internal borders, her decision has wider repercussions. Were Germany’s borders rigorously enforced through passport checks, her decision might be perceived as evidence of realism. The same could conceivably be argued on behalf of those leaders who abandoned the law to counter its intended purpose. Whether the decision maintains or restricts the right of asylum, ignoring a law that applies across all of Europe raises questions about rights versus borders.

As thousands of Syrian migrants trek across Hungary with their sights set on Germany, France and Britain, Budapest has also decided not to honour the Dublin Agreement by building a wall to keep asylum seekers out. Slovakia has decided to accept only migrants who are Christian, denying entry to all others, perhaps planting the seeds of future division in Central Europe on religious grounds.

Meanwhile, in western Ukraine, areas that were once part of Poland and Lithuania, want to join the European Union, while eastern Ukraine is divided between remaining as a part of Ukraine or joining Russia, resulting in a civil war in the industrial part of the country. United Nations figures for the end of August 2015 indicate 1.3-million people displaced inside Ukraine, and 867-thousand people who have sought refuge elsewhere, most of them across the border in Russia. The number of desperate people in need of asylum is not only growing, it extends across western Europe up to the Russian border, and there’s little indication that it will end soon. “Although in most countries the probability of conflict is not as immediate as in Ukraine, most European societies appear increasingly fragmented. Mutual understanding between groups decreases, and common interests are harder to find.” (5)

Setting aside the legally-sanctioned easing of borders inside Europe, the question of international borders comes into sharper focus. With the steadily increasing growth of such a mass exodus of asylum seekers and would-be migrants from so many countries over the past few years, it’s as if Europe’s international borders have ceased to exist. In practical terms, they are turning out to be little more than lines on a map. In terms of state integrity, the steady increase of refugees may be a harbinger of more serious things to come. Given the reaction of various European governments ranging from building fences, violating asylum laws to reject migrants, or ignoring the law to accept them, Europeans will eventually have to decide what is more important, the laws of the state or the laws of the Union? If we project this crisis and its fallout five or ten years into the future, we may well see the redrawing of boundaries depending on how various actors react to events. As history shows, redrawing borders is seldom peaceful.

Setting aside the legally-sanctioned easing of borders inside Europe, the question of international borders comes into sharper focus. With the steadily increasing growth of such a mass exodus of asylum seekers and would-be migrants from so many countries over the past few years, it’s as if Europe’s international borders have ceased to exist. In practical terms, they are turning out to be little more than lines on a map. In terms of state integrity, the steady increase of refugees may be a harbinger of more serious things to come. Given the reaction of various European governments ranging from building fences, violating asylum laws to reject migrants, or ignoring the law to accept them, Europeans will eventually have to decide what is more important, the laws of the state or the laws of the Union? If we project this crisis and its fallout five or ten years into the future, we may well see the redrawing of boundaries depending on how various actors react to events. As history shows, redrawing borders is seldom peaceful.

Bibliography:

(1)www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/germany/11821822/Germany-drops-EU-rules-to-allow-in-Syrian-refugees.html

(4) Kingley, P. www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2015/aug/10/10-truths-about-europes-refugee-crisis

(5) de Voogd, J. Redrawing Europe’s Borders, Europe Under Fire, Winter 2014/2015

Tags: Angela Merkel, asylum, Austria, Balkan States, boundaries, Dublin Agreement, EU, European Union, Germany, Greece, Hungary, immigration, Lebanon, Macedonia, Mare Nostrum, Mediterranean, Russia, Schengen Treaty, Serbia, Slovakia, State laws vs Union laws, Sweden, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine

The Syrian passport that was found at the Bataclan concern hall in Paris seems more of a set-up aimed at deliberately enflaming public opinion against the mass of immigrants who have made their way through Europe. It is more likely part of a plan to destabilise crowds in Europe than a gunman simply losing his passport.

One of the Islamic terrorists involved in the Paris attacks this week purportedly entered Greece with a group of boat immigrants in early October. This will exacerbate fears that ISIS has hidden hordes of fighters among the surge of immigrants entering Europe.

Germany has shown a high level of tolerance in the face of an overwhelming problem. However, Germany restricted entry this week-end because it was overwhelmed. Berlin appears to be engaged in a step-by-step approach to try to deal with the problem. Sweden appears to be doing the right thing in humanitarian terms by accepting more refugees. The remaining countries in western Europe continue to be paralyzed by varying levels of fear, some of it based on the sheer numbers of incoming refugees, by xenophobia and fear of increased terrorism, and in some cases outright xenophobia and fear of being overrun by Islam. In this respect tolerance intersects with identity politics. The countries of Eastern Europe have not yet dispelled an inherent distrust caused by decades of living under repressive governments so remain suspicious of outsiders, and are afraid of losing their identities. This is evident in Hungary which wants to stop the flow of refugees with a four-metre fence along its border, or in Slovakia, which accepts Christian refugees who, at least, have the same religious practices. Whether the Schengen accord remains intact after the ad hoc actions of various European countries remains an open question. However, strengthening the borders around the European Union will only serve to push the problem onto countries such as Serbia, Greece, Italy who are less equipped to deal with it. Open borders under the Schengen Accord is a reflexion of openness. Maintaining border controls is a reflexion of realism. Building fences lead to growing frustration and strife. Europe has yet to find the balance.

Human migration is one of the dynamics of history.

What is unfolding in the E.E.C., is a continuation of the many human migrations that

have occurred repeatedly since the emergence of modern humans.

Will this affect the E.E.C.? Yes!

What will be the result? Change!

How the change will manifest, may be changing borders, laws, and alliances.

In the future, the same dynamic forces will change the borders and laws of North America.

At 66 years old, I may livelong enough to witness it.

A continuous large influx of emigrants on only a few countries is not acceptable. A percent should be applied to all.

The root of the problem of course is the middle east countries instability. Our failure in Afghanistan shows the difficulty in bringing peace to these countries.

Guns don’t work. It has to come from the people themselves through, negotiation even with the terrorists themselves.

The main cause of unrest in the middle east is capitalistic greed with its retribution supported by religious beliefs.