Sierra Leone: A Dream of Freedom

In March 1991, warlord Foday Sankoh of Sierra Leone and the Rebel United Front invaded Sierra Leone from a part of Liberia controlled by Charles Taylor, who then led the insurgent National Patriotic Front of Liberia. It was the beginning of a nine-year civil war. However, the events that led to the war started long before.

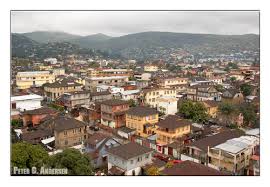

Freetown

Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone was founded in 1792 by black settlers from Nova Scotia who had a dream of living in freedom. However, Freetown was taken over by the British in 1808 who denied blacks their agricultural land. Bøås (2001) describes the makeup of Freetown as the descendants of the original 1200 settlers plus 70,000 blacks rescued from slave ships, plus European administrators who together became known as Creoles. By the second half of the 19th century they had “developed their own language, krio, built up Freetown and established themselves in some of the most important positions in society” (Bøås, 2001, p. 705). Outside Freetown, southern Sierra Leone is populated by the Mende tribe, while the north is populated mainly by the Temne. In 1951, the Sierra Leone People’s party was formed. “The SLPP claimed to be the national party, transcending regional and linguistic divisions, and it included some Creoles among its rank and file and leading hierarchy, but it was to a large extent a challenge to Creole domination and pretensions” (Bøås, 2001, p. 707). In the preceding 30 years, Sierra Leone’s economy had gradually shifted away from such products as coffee and cocoa beans to more lucrative products such as iron ore, bauxite and diamonds. This mineral wealth happened to be in northern areas that were formerly ignored both economically and politically.

Coup d’État

In 1960, a trade union leader, Siaka Stevens, formed the All People’s Congress which enfolded a wide range of dissidents and youth who felt excluded from society. This was especially true for those members who lived in the north of the country, who felt that élites from the south controlled economic life.

In 1967, Stevens and his APC, with the help of ethnic groups in the north narrowly won Sierra Leone’s general election and was named prime minister. However, shortly thereafter, a coup d’état drove him to neighbouring Guinea where he had already prepared, and was training, a paramilitary unit in case he didn’t win the elections. We see here the first hint of what lay in store for Sierra Leone.

A year later, non-commissioned officers overthrew the military junta in Sierra Leone and returned Stevens and the APC to civilian rule. By now, his paramilitary unit was well-trained in revolutionary techniques and how to disrupt the operations of a country. Stevens called them his Special Security Unit and placed them above the National Police Force and below the National army. Later, he withdrew all weapons from the army leaving the SIU in charge. “The SIU, comprising Steven’s guerrilla army would soon become notorious for violence, and suppression of civil liberties throughout the land, especially in those cases outside the northern province” (Kposowa, 2006, p. 39). In 1978, after systematically stifling or killing those who disagreed with him, or who even represented a threat, Stevens made changes to the country’s political structure. He introduced a one-party system, essentially turning parliament into a powerless entity that rubber-stamped his every decision. In 1985, Stevens hand-picked his successor, Joseph Momou, and retired having essentially installed his own private army, crushed anyone who disagreed with him, destroyed the education system through neglect and abandoned the country’s youth to its own devices. These events had taken place one at a time, slowly at first, then layering one upon the other until their accumulated weight left the country ripe for civil war.

In the meantime, Foday Sankoh, a former corporal in the Sierra Leone army travelled to Libya where he trained in a guerrilla camp. He also met and became a close friend of Charles Taylor, who was later to become the president of Liberia. When Sankoh attacked the Momou government in 1991, it was with Taylor’s support.

In the meantime, Foday Sankoh, a former corporal in the Sierra Leone army travelled to Libya where he trained in a guerrilla camp. He also met and became a close friend of Charles Taylor, who was later to become the president of Liberia. When Sankoh attacked the Momou government in 1991, it was with Taylor’s support.

Another factor leading to civil war was the high proportion of uneducated youth in the country. If youth are treated well, cared for and educated, they become a positive resource that can help a country grow with inherent respect for people, laws and institutions. This was not the case in Sierra Leone where the government failed to invest in adequate education for its young population. The result was that youth had little or no access to basic education, let alone technical or vocational schools. There was also little opportunity for jobs, careers or advancement. What jobs there were, were reserved for the élite in the south who had already acquired wealth from the cocoa and coffee bean trade of earlier years. The élite also ensured that their children had a good education. These educated children received the most coveted of jobs, namely positions in the country’s civil service. For those with little or no education, there was massive unemployment. Much of what economy there was, was informal and based on mining and trading illegal diamonds. “It was these unemployed, illiterates, school dropouts, the hungry, the disposed, and other politically-alienated youth that swelled the ranks of Foday Sankoh’s RUF rebel army when he launched his attack on Sierra Leone in March 1991” (Kposowa, 2006, p. 43). Although Sierra Leone was a wealthy country in terms of resources, the gradual collapse of institutions needed to help the country and its people led to extreme poverty. A rich country with functioning institutions, courts, respect for the rule of law, education, and opportunity might have prevented what happened in Sierra Leone. That would have allowed the people of Sierra Leone to gradually accumulate wealth. “Widespread wealth is likely to act as a general deterrent to participation in major violence” (Crocker, 2003, p. 60). However, opportunity and the taboo against killing gradually vanished as the SIU ruthlessly suppressed dissidents, and anyone else who questioned them as well as those who failed to give them enough money at the impromptu checkpoints that were set up throughout the country.

Ripe With Promise?

Ripe With Promise?

For those who remember Sierra Leone when it was a British colony, Freetown was a vibrant safe city and the country ripe with promise. When Sierra Leone gained independence in 1961, it had a functioning British legal system, a parliamentary system, an educational system, an army, a police force, choice agricultural land and a profitable source of income in minerals such as bauxite, gold and diamonds. The country was so profitable that “its currency at independence was strong, and in fact until the mid-1970’s, the Leone was stronger than the U.S. dollar” (Kposowa, 2006, p. 42). The civil war in Sierra Leone was not only noteworthy for the fall from grace of a prosperous country, but for its viciousness. Conflict in Sierra Leone was marked by abductions, unusually cruel and violent rapes, torture, and the amputation of arms, hands, feet, and legs. Those responsible for such gruesome deeds were “driven by boredom, greed and the thrill of violence” (Hammer, 1995, p. 10).

The answer to why such poverty, exclusion, repression and violence occurred and gradually overcame a civilisation that was offering slow but steady progress for a substantial portion, if not all of its people, may be found by taking a closer look at the traditional patrimonial politics of Africa. Charles Taylor, an African warlord, is currently on trial in The Hague for war crimes in Sierra Leone. However, there are others who preceded him in infamy whose names are equally familiar such as Uganda’s Idi Amin, or South West Africa’s Sam Njoma, or Somali’s Mohammed Siad Barré who was deposed in 1991. Two years later, another warlord, Mohammed Farrah Adid became prominent in Somalia, attacking U.S. peacekeepers in the now well-known incident portrayed in the film “Blackhawk Down”. The case of Taylor is representative of warlords across Africa. People served him, sometimes even turned against him. There were also people with whom he dealt with and befriended like Foday Sankoh. This begs the question then what system of values or understandings do African warlords follow as they exert their power? What drives them? Bøås (2001) says African warlords, or personal lords and would-be leaders, are variants of Machiavelli. “The African prince is an astute observer and manipulator of lieutenants, henchmen and clients; he either rules jointly with other oligarchs or he rules alone but cultivates the loyalty, co-operation and support of other ‘big men’. The basic motivation for seeking political power is neither ideology nor national welfare but the desire to acquire aid to ensure the well-being of one’s own group” (Bøås, 2001, p. 699). The entire raison d’être of warlords then is survival by taking power, crushing dissent and ensuring that no one else is in a position to seize power. Although cultural identity played a role in Sierra Leone’s civil war, it was less the major indications of race, religion or language than a return to the basic warlord culture that was so prevalent elsewhere in Africa from Ethiopia to Somalia, and from the Congo to South-West Africa, now known as Namibia. If anything, the African warlord offered protection, a sense of identity and a chance to regain what people had before. “Ethno-political groups organise around their shared identity and seek gains or redress of grievances for the collectivity” (Crocker, 2003, p. 168). There were other factors that also led to violent conflict. “Three types of incentives prompt political action by identity groups: resentment about losses suffered in the past, fear of future losses, and hopes for relative gains” (Crocker, 2003, p. 169). This is evident when considering the loss of education, loss of opportunity and subsequent jobs, and loss of dignity for the country’s northern groups at being deprived of what the élite in the south could take advantage of. “The greater a group’s collective disadvantages vis-à-vis other groups, the greater the incentives for action” (Crocker, 2003, p. 169)

No Tolerance, No Democracy

In western terms, what took place in Sierra Leone could be referred to as a growing pathological abnormality which, over time became so strong, it finally reached the point where those who were responsible for violence in Sierra Leone lost all sense of moral restraint. Their victims were caught up in a current against which they had little control and no hope. In their efforts to determine the cause of civil war, social scientists have looked into such reasons as competing groups with inflexible interests, and greed leading them to conclude that immaturity is partly responsible. “Scientific investigators …tended to attribute war to immaturities in social knowledge and control, as one might attribute epidemics to insufficient medical knowledge or to inadequate public health services” (Crocker, 2003, p. 31). However, immaturity in the western sense does not entirely account for what happened in Sierra Leone. Another reason for the outbreak of civil war is the weakening of democratic institutions which can no longer tolerate different points of view. In Sierra Leone, a once vibrant, functioning bi-cameral parliament became progressively weaker as parliamentarians feared for their lives if they challenged the president. Stevens, backed by the SIU, essentially turned parliament into a group that passed laws only for him.

The causes of civil war in Sierra Leone are complex. “A study of the world’s civil wars since 1960 found that the most important risk factors were poverty, low economic growth and a high dependence on natural resources, such as oil or diamonds” (Economist, 2004). Although that is true for Sierra Leone, the code of the African warlord cannot be dismissed as a major factor in the war. “From the time of Thucydides until that of Louis XIV there was basically only one source of political and military power – control of territory, with all the resources in wealth and manpower that that provided.” (Crocker, 2003, p. 34). Sierra Leone’s territory happened to have bauxite, gold and especially diamonds. The RUF was essentially playing at ethnic politics while Charles Taylor helped them in exchange for controlling Sierra Leone’s diamond mines. In Freetown, a new civilian government elected in May 1997 was quickly overrun by a new rebel group, the Armed Forced Revolutionary Council (AFRC). The UN Security Council then imposed an oil and arms embargo on Sierra Leone, and the Economic Community of West African States sent in soldiers under ECOMOG (Military Observer Group of the Economic Community of West African States) to restore the government to power” (Crocker, 2003, p. 334). This did not resolve the situation since the RUF controlled the rest of the country. RUF forces then joined the AFRC in seizing Freetown in 1998. ECOMOG forces once again restored the civilian government to power. Foday Sankoh came under international pressure to negotiate and the war ended with the controversial Lomé Accord in 1999. Several months later, a tired, frustrated angry mob stormed Sankoh’s villa. While Sankoh and his rebels fled, the crowd found documents that proved that Sankoh and his Revolutionary United Front had been trading diamonds for guns. The documents revealed that they were helped by Charles Taylor of Liberia, and Burkina Faso, even after the controversial deal was signed. The Lomé Accord “gave Sankoh a role in government as head of a proposed commission responsible for marketing the country’s diamonds” (Coping with Conflict, 2004, Economist). After this information was revealed, the Lomé Agreement collapsed. In 2000, the United Nations, which had by this point authorised several mainly observer missions in Sierra Leone, sent in UNAMSIL, or the United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone. UNAMSIL eventually grew to encompass 17, 500 military personnel, which finally brought peace to the country. The last UNAMSIL peacekeeper left Sierra Leone in 2005. However, a “U.N. presence will still remain in the country and an international military and training team, led by the United Kingdom, will also stay at least until 2010 to train the country’s armed forces” (Bell, 2005, p. 43). As a result of talks between the civilian government in Freetown and the United Nations, the Special Court of Sierra Leone was created to ensure that those responsible for the carnage in Sierra Leone would be held accountable. “The Civil war in Sierra Leone and the country’s ultimate emergence out of the conflict compellingly indicate once again that peace is not sustainable without justice” (Bell, 2005, p. 43). Sierra Leone has been returned to peace but still remains in a precarious state. Over the next few years Sierra Leone represents a challenge to the international community. It must ensure that the country can develop to the point where its own economy and institutions such as governmental, educational and commercial can finally break the conditions that enabled the warlord culture to survive. Charles Taylor, who controlled Liberia from 1997 to 2003 was forced to go into exile in Nigeria after brutalising not only his own country, Liberia, but also much of neighbouring Sierra Leone. When the international community put pressure on Nigeria to turn Taylor over to the Special Court in Sierra Leone, he tried to flee to Cameroon where he was arrested and flown to Sierra Leone to stand trial. However, in the weeks before Taylor’s arrest, Sierra Leone asked the United Nations war crimes trial in The Hague if it would try him due to “concerns that his presence in Sierra Leone could lead to more unrest” (Time, 2006).

The concerns appear to be justified since Taylor is alleged to have fomented war in three countries that left as many as 300,000 people dead and thousands more raped and maimed” (Time, 2006). The detailed list of crimes with which Mr. Taylor is charged is long. “Charles Taylor faces 11 charges all woven around ‘helping or supporting the former Sierra Leonan rebel group, Revolutionary United Front (RUF)..” (Boateng, 2007, p. 20). Taylor has been charged with war crimes, crimes against humanity, sexual slavery, conscripting children under the age of fifteen as soldiers, looting, violence and murder. The trial is currently underway and will likely conclude within the next year or possibly two. What is less uncertain is how long it will take for Sierra Leone to recover from its decade of war and Freetown can turn into the place black settlers from Nova Scotia dreamed of when they founded it 315 years ago. Foday Sankoh died relatively peacefully of a heart attack in July 2003, compared to the peaceful death he denied thousands of his victims.

Bibliography:

Boateng, O. (2007, February). Will Charles Taylor get a fair trial?. New African, Retrieved June 11, 2007, from Academic Search Premier database.

Bell, U. (2005, December). Building On A Hard-Won Peace. UN Chronicle, 42(4), 42-43. Retrieved June 11, 2007, from Academic Search Premier database.

Bøås, M. (2001, October). Liberia and Sierra Leone – dead ringers? The logic of neo-patrimonial rule. Third World Quarterly, 22(5), 697-723. Retrieved June 12, 2007, from Academic Search Premier database.

Coping with conflict. (2004, January 17). Economist, Retrieved June 12, 2007, from Academic Search Premier database

Crocker C., Hampson F., Aall P. (2003), Turbulent peace, Washington, D.C. : United States Peace Institute.

Hammer, J. (1995, April 10). TEENAGE WASTELAND. New Republic, 212(15), 10-10. Retrieved June 12, 2007, from Academic Search Premier database.

Kposowa, A. (2006, March).Erosion of the Rule of Law as a Contributing Factor in Civil Conflict: The Case of Sierra Leone. Police Practice & Research, 7(1), 35-48. Retrieved June 11, 2007, from Academic Search Premier database.

Robinson, S., da Costa, G., & Dwyer, J. (2006, April 10). Snaring a Strongman. Time, 167(15), 49-49. Retrieved June 11, 2007, from Academic Search Premier database.

Tags: Charles Taylor, Civil war, Democracy, Foday Sankoh, Sierra Leone, Tolerance