On The Move

Since the end of the Second World War, we have become accustomed to seeing the influence of the United States and Britain in the Middle East. In 1943 President Franklin Delano Roosevelt had already declared that « the defence of Saudi Arabia was vital to the defence of the United States. » (1) On his way home from the Yalta Conference in February 1945 after meeting with Stalin and Churchill, Roosevelt met with King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia on board the USS Quincy. Their agreement, the Quincy Pact, was not revealed for several years. It offered Saudi Arabia US protection from external enemies in exchange for secure access to future supplies of oil. Although there is some question as to whether they actually signed such an accord, the fact remains that the US has provided protection to the Saudi Kingdom, and received billions of barrels of oil since that time, echoing Roosevelt’s sentiments of 1943.

Iran

America and Britain were behind the ouster of Iran’s democratically-elected government in 1953 when the Shah replaced Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh with Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi in a coup d’état. A declassified CIA internal history entitled « The Battle for Iran » released in 2013 states “The military coup that overthrew Mossadegh and his National Front cabinet was carried out under CIA direction as an act of US foreign policy conceived and approved at the highest levels of government.” The documents describe how the US and Britain engineered the coup, codenamed TPAJAX by the CIA and Operation Boot by Britain’s MI6.” (2) The US and Britain considered Mossadegh a liability. According to Iranian-Armenian historian Ervand Abrahamian, author of The Coup: 1953, the CIA and the Roots of Modern US-Iranian Relations, says the coup was designed “to get rid of a nationalist figure who insisted that oil should be nationalised”. (3)

Oil became the underlying raison d’être in the conflict between the US and Iraq in 2003. The prélude to the conflict was the Gulf War, also known as Operation Desert Shield, when the United States and a coalition of international forces took part in Operation Desert Storm to counter the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. The next stage was the invasion of Iraq in March 2003 and the military occupation of the country until the US withdrawal of forces in 2014. Between 2003 and 2011, an estimated half-million Iraqis died in the conflict. (4) Although the invasion was based on a false premise to rid Iraq of weapons of mass destruction, oil companies from the United States, Britain, Holland, Russia, and China were quick to take advantage of Iraq’s oil wealth. (5)

In March 2017, Saudi Arabia and China signed commercial agreements worth up to 65-Billion dollars. The agreements, which include renewable energy and oil investments also mark a closer diplomatic rapprochement between the two countries. For Saudi Arabia, the agreements were part of its « Saudi Vision 2030 » policy to diversify its economy. For China, ensuring a continued supply of oil was also an opportunity to expand its diplomatic influence. Saudi’s King Salman expressed hope that China would increase its role in the Middle East, saying that « Saudi Arabia is willing to work hard with China to promote global and regional peace, security and prosperity. » (6) Although China’s president Xi Jinping spoke in terms of expanded trade with Saudi Arabia, his country’s actions in the region show Beijing’s desire to play a much greater role in international affairs. Several months later on the 11th of July 2017 China officially dispatched a fleet of military personnel from the port of Zhanjiang in southern Guangdong province to its first overseas base in Djibouti on the Red Sea beside the U.S. Lemonnier Base. According to the Xinhua news agency the so-called “support base will ensure China’s performance on missions, such as escorting, peace-keeping and humanitarian aid in Africa and west Asia.” (7) Xinhua says the base in Djibouti will also perform other functions such as military cooperation through joint exercises, evacuation and protection of overseas Chinese, rescue operations, as well as jointly maintaining security of international strategic waterways.

Silk Road Economic Belt & Maritime Silk Road

Four years earlier in the fall of 2013, President Xi announced plans to build a new Silk Road Economic Belt, as well as a Maritime Silk Road between Europe and China, together known as the Belt and Road Project. However, we see the beginning of China’s thrust in world affairs as early as March 1997 when Beijing’s National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and a consortium of mainly Asian oil companies signed a deal with Khartoum to develop oil reserves in Sudan. After the end of the civil war between Sudan and South Sudan in 1995, Chinese businesses slowly set up shop in Juba. A year later China opened a consulate there. However, without the capability to project its power, China was reluctant to engage in efforts to resolve conflict. Beijing slowly began to stretch its policy of non-intervention when conflict did break out by organising several large-scale evacuations of nationals from countries in the region. In 2008, China used its influence in Sudan and in the UN Security Council to send UN peacekeepers to Darfur. When civil war erupted in Libya in 2012, China’s evacuation of 36-thousand Chinese nationals was a turning point. By sending aircraft and frigates through the Red Sea and the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean for the first time. « China’s evacuation of its citizens generated national pride and increased both its people’s and its investors’ expectations about Beijing’s global profile. …China extended the boundaries of its time-honoured diplomacy, suggesting growing willingness to take action when its interests are threatened. » (8) Chinese naval vessels in the Mediterranean was perceived by some in the west as Beijing gaining access to NATO’s lake. However, as stated in China’s state-controlled media, « the Mediterranean needed to become accustomed to China’s naval presence ». (9) China has since invested in shipping companies around the Mediterranean and has been expanding ports in Greece (Piraeus), France, Spain and Tripoli. It has also invested in rail and air terminals in Portugal, and Italy. (10)

(For detailed look at Maritime Silk Road, http://quinndiplomacy.com/2015/03/20/gameplan/

Syria & Turkey

One of China’s allies now also has greater access to the Mediterranean. In January 2017, Damascus and Moscow signed an agreement to increase the size of Russia’s Mediterranean naval facility in the Syrian port of Tartus. The accord is for 49 year but can be extended by another 25 years. The Russian news agency, Tass, says the expansion means as many as 11 warships, including nuclear-powered vessels, can be berthed simultaneously in the port, more than doubling the facility’s current capacity. Tass quotes Igor Korotchenko, the editor-in-chief of the National Defence journal as saying that the enhanced facility « will be a major factor to deter unfriendly actions against Russia by any regional and international players. » (11) Syria is one of the traditional western points of the ancient Silk Road because of its geographic location. Before civil war broke out in Syria, China was already using the country to ship goods into Iraq, and Lebanon from its hub known as China City – an area in the Adra Free Zone industrial park northeast of Damascus. China’s National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) has also considerable investments in two of Syria’s largest petroleum companies having agreed to help Damascus explore and develop its oil reserves. (12)

Turkey, immediately north of Syria, is another strategic point on the traditional Silk Road giving access to the Black Sea and markets in southern Russia and Ukraine and to the Mediterranean, the gateway to Europe. In May 2017, shortly before Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdogan was preparing for his fourth visit to China in two years, China’s ambassador to Turkey said Beijing was ready to discuss Turkey’s membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Yu Hongyang said “China understands Turkey’s intention of becoming a member of the SCO, is ready for Turkey’s membership…in consultation with other member countries.” (13) If Turkey becomes a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, while maintaining its membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, it could well result in a conflict of interest between east and west, contributing to western destabilisation.

Chinese Rail Link Across Eurasia

Another sign of Beijing’s progress to expand its trade and influence across Eurasia is China’s new rail service with Europe. When the first freight train arrived in London from Wiwa in eastern China in January 2017, it caught the attention of businesses eager to sell their wares to a larger market. The train made the 12,070-kilometre journey in 18 days. On the way it rolled through Kazakhstan, Russia, Belarus, Poland, Germany, Belgium and France before crossing under the English Channel into Britain. Since then, London has become the 15th European city to have a direct rail link with China. Even though the route is longer that Russia’s Trans-Siberian railway, it’s one thousand kilometres shorter than the link between China and Madrid, which opened in 2014. According to the China railway Corporation, its services are cheaper than air transport and quicker than shipping. (14) British officials say the new rail line is part of greater trade links to China in preparation for its exit from the European Union, due on the 29th of March 2019. Beijing’s rail expansion also extends into parts of the Middle East. China signed an agreement with Israel in 2012 to build a light rail link from Tel Aviv to Eilat on the Gulf of Aqaba, as well as a rail line for cargo between the Mediterranean port of Ashhod and Eilat. Strategically this offers an alternative to the Suez Canal in the event of any future instability caused by the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Beijing has also signed agreements with Cairo to build a high-speed railway linking Cairo, Alexandria, Luxor and Hurghada on the Red Sea. China has also been enlarging the Port of Sudan on the eastern side of the Red Sea, enabling it to ship trade or military goods to Sudan, East Africa and the Horn of Africa. Since 2009 when China overtook the United States as Africa’s number one trading partner, the Middle East has become a strategic region that connects markets in Europe, Africa and Asia. Africa is especially important in China’s foreign policy agenda because of its vast energy reserves needed to fuel the country’s economic growth. Although the public emphasis is on trade, China’s expansion of rail links across Eurasia and the Middle East, and eventually to Africa, also serves as an additional means to project its power across continental distances to protect its interests. “The People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s General Logistics Department (GLD) is actively participating in the design and planning of China’s high-speed railway, with military requirements becoming part of the development process. Indeed, the GLD is looking to implement rapid mobilization and deployment of troops via high-speed rails once they are completed across Eurasia.” (15)

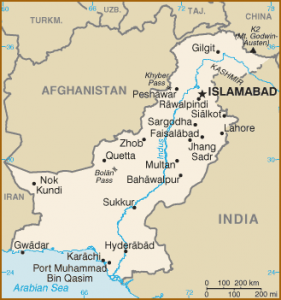

Pakistan

The Asian portion of China’s Silk Road initiative is equally ambitious. Pakistani and Chinese companies are building a railway, as well as an 800-kilometre highway that will link the port of Gwadar on the Arabian Sea to Kashgar in western China. Through an initiative known as the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, or CPEC, Beijing is also building electrical power stations, and a pipeline that will carry oil from the Persian Gulf through Iran to western China. Several countries speak in glowing terms of China’s Road and Belt Initiative. Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn of Ethiopia called the project unique, historic, extraordinary and momentous, seeing China as an ally in the fight against poverty. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif called it the “dawn of a truly geo-economic revolution”. Pakistan’s age-old enemy India disagrees, calling China’s initiative a colonial enterprise that will infringe on other countries’ sovereignty. China’s reaction was swift. The state-controlled Xinhua new agency, published a commentary saying that “China harbours no intention to control or threaten any other nation, seeing its actions as a chance not “to assert a new hegemony, but an opportunity to bring an old one to an end”. (16)

Chinese bankers overseeing the Shanghai-based New Development Bank set up by BRICS in 2014 will play a key role in the success of the Belt and Road Initiative, and some have urged caution. Peter Cai, a fellow at Australia’s Lowy Institute for International Policy says their appetite to fund infrastructure projects and their ability to handle the complex investment environment beyond China’s border will shape the speed and the scale of the initiative. Mr. Cai says there is general recognition that the project will take ten years and many are treading carefully. However, given that the United States, and England through its decision to leave the European Union (Brexit) “are both retreating genuinely or symbolically from their commitment to globalisation” Mr. Cai feels that this is a good time for China to promote itself as the new champion of globalisation.” (17)

A shift in western diplomacy

China’s growing thrust across Eurasia comes as two of the planet’s major power blocs, the European Union and the United States, find themselves at a crossroads. Not only is England involved in Brexit talks to leave the EU, western economic sanctions imposed on Russia over the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in eastern Ukraine deprive the EU of trade opportunities in central Asia. This creates pressure on the EU to choose between readily available energy from Russia and Ukraine or to remain in the “Atlantic camp”. In May 2017, shortly after the U.S. President, Donald Trump, met Germany’s Chancellor, Angela Merkel, at the G7 Summit in Italy, Merkel said that Europe could no longer rely on the US or the United Kingdom and must ‘fight for its own destiny.” Her statement marked a dramatic and unexpected shift in post-war western diplomacy. (18)

China’s growing thrust across Eurasia comes as two of the planet’s major power blocs, the European Union and the United States, find themselves at a crossroads. Not only is England involved in Brexit talks to leave the EU, western economic sanctions imposed on Russia over the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in eastern Ukraine deprive the EU of trade opportunities in central Asia. This creates pressure on the EU to choose between readily available energy from Russia and Ukraine or to remain in the “Atlantic camp”. In May 2017, shortly after the U.S. President, Donald Trump, met Germany’s Chancellor, Angela Merkel, at the G7 Summit in Italy, Merkel said that Europe could no longer rely on the US or the United Kingdom and must ‘fight for its own destiny.” Her statement marked a dramatic and unexpected shift in post-war western diplomacy. (18)

From the U.S. action in Iraq in 2003 to its ill-fated efforts in Libya, to the abandonment of a decades-long relationship with Egypt, the credibility of the United States and its guarantee of security has considerably eroded. Its isolationist view, lack of a strong response to China’s reclaiming of islands in the South China Sea, one of the world’s strategic waterways, and its inability to prevent North Korea from becoming a nuclear power has done little to reassure its allies. What the United States decides to do next will have long-term implications, not only for security in the Middle East and in East Asia, but for the world. Allies, power blocs, trading partners are all watching and waiting to see what happens over the next four years. Will the United States stand up to guarantee security and stability on the planet? Will the Washington Consensus give way to the Beijing Consensus? Is this an historic cycle where the sun now shines on the Middle Kingdom? We do indeed live in interesting times.

Tags: China, China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Iran, Middle East, People's Liberation Army and China's rail Eurasia rail network, Port of Tartus, Saudi Arabia, Shah, Shift in western diplomacy, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, US credibility

Interesting article. Will the United States stand up to guarantee security and stability on the planet? I think they will. Even if the current political climate suggests it will get involved, the security of the U.S. is based on the security of its “traditional allies” (UK, EU…). China is doing what’s in its best interest. They have a long-term vision with plans 50 years+. They can operate in ways the U.S. and western democracies can’t. However it will have it own share of problems. China is actually very divided. There’s coastal China, where the wealth and power is, and central/rural China, where it’s pretty much just poverty. They have a huge wealth gap that could cause social unrest. Remember this was Mao’s land.

Is it really the U.S. vs China? Or is it what’s good for the U.S. is good for China? Their economic ties are too important. The Chinese have calculated that they need 30 to 40, maybe 50 years of peace and quiet to catch up, build up their system, change it from the communist system to the market system. I believe the Chinese leadership has learnt that if you compete with America in armaments you will lose. You will bankrupt yourself. So avoid it, keep your head down, and smile for 40 or 50 years. China will inevitably catch up to the US in absolute GDP. But it’s creativity may never match Americas, because its culture does not permit free exchange or contest of ideas.

Enlightening post on what China is up to these days as it hones its skills and strategies as a forthcoming superpower. The way this new imperialist on the world stage will manoeuver in the following years and decades will be something to watch.

Very interesting overview of China’s quiet march to takeover leadership

I was particularly interested in the way China is merrily extending its influence while the world is focused on Trump’s handshakes.

Hmmm… and what hegemony is China proposing not to replace but to end? That scenario is quite plausible but I wonder why China has never chosen to extend itself on a global scale over the course of 4,000 years of empire (or even to let Zheng He off the leash in the 14th century.)? Foreign adventures can only divert attention from internal tensions for so long. Obama’s premise was that Americans have no stomach for the effort and expense of global empire. Trump seems to fancy the role of cranky rhinoceros, dangerous but squinty-eyed.rhinoceros. Germany, Turkey, India and Iran . . . too many loose pieces on the board for anyone’s hegemony.