Game Plan

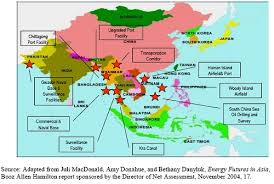

Woody Island and Mischief Reef sound like names out of a Hardy Boys mystery, complete with mysterious goings-on to capture our imagination. However, instead of being off the shores of Bayport, the home of our amateur sleuths, they are part of the Paracel and Spratly island chains in the South China Sea. China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia and Taiwan all claim the islands because they are not only believed to contain oil and gas deposits, their placement would also confer greater influence over one of the world’s most strategic waterways.

These hundreds of islands are little more than reefs, shoals and sandbars that normally merit little notice. However, since the summer of 2014, China has sent dredgers to an estimated half-dozen islands in the Paracel and Spratly chains to suck up sand from the shallow depths to build the reefs up. According to surveillance photos published by the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, an arm of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, China has started building installations on now reclaimed islands. (1)

The reason behind China’s actions can be summed up in the words of former Chinese president Hu Jintao. In November 2003, he said that four-fifths of the oil that China needed to develop and operate its industry flowed through the Malacca Strait, what he called the Malacca Dilemma. (2) The U.S. 6th Fleet controls shipping through the strait, leaving China vulnerable to economic paralysis should a geopolitical crisis result in a naval blockade of the strait. Short of declaring war on the United States, which China would be sure to lose under current conditions, Beijing has no option but to engage in a long-term strategy to secure its economic interests.

The reason behind China’s actions can be summed up in the words of former Chinese president Hu Jintao. In November 2003, he said that four-fifths of the oil that China needed to develop and operate its industry flowed through the Malacca Strait, what he called the Malacca Dilemma. (2) The U.S. 6th Fleet controls shipping through the strait, leaving China vulnerable to economic paralysis should a geopolitical crisis result in a naval blockade of the strait. Short of declaring war on the United States, which China would be sure to lose under current conditions, Beijing has no option but to engage in a long-term strategy to secure its economic interests.

Part of that strategy involves the Paracel and Spratly islands. By dredging sand and patiently building up reefs in the South China Sea, Beijing hopes to strengthen its claim to the islands. As shoals and reefs gradually become islands, critics in Vietnam, the United States and the Philippines are concerned that China will use them to set up better surveillance technology, air strips and resupply stations for government ships. Based on the adage that possession is nine-tenths of the law, the presence of Chinese radar installations in the centre of such an important waterway is a step toward consolidating greater influence in the region, and the eventual projection of Chinese power across the Western Pacific. “The new islands could allow China to claim it has an exclusive economic zone within 200 nautical miles of each island, which is defined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. (3) China maintains it is doing nothing wrong. In May 2014, a spokeswoman for the foreign ministry in Beijing, Hua Chunying, using the Chinese name for the Spratly Islands, said “China has indisputable sovereignty over Nansha Islands,” giving it the right to build what it wants. (4)

China – Vietnam

This is not the first time China has taken action in the South China Sea. On the 2nd of May 2014, Beijing set up a 40-story oil rig near the Paracel islands in an area Vietnam considers its exclusive economic zone. For the next two months China and Vietnam engaged in a standoff as an armada of Chinese coast guard ships, surveillance ships, frigates, fishing boats, and a helicopter prevented Vietnamese fishing boats and government vessels from going into the area.  As the standoff escalated, relations between China and Vietnam rapidly deteriorated. Anti-China riots broke out in Vietnam as protesters set fire to factories forcing thousands of Chinese to flee the country. A foreign policy meeting in June failed to reach any consensus, with Beijing refusing to back down, and Vietnam vowing to defend its territory. At one point, a Chinese ship damaged a Vietnamese fishing boat. Chinese crewmen then arrested six Vietnamese fishermen for allegedly fishing in Chinese waters. On the 2nd of July 2014, China’s National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) moved the oil rig back into Chinese territory. According to the company’s website, the rig discovered oil and gas, allowing China to complete its mission a month earlier than planned. The website hinted at future moves in the area saying that the data would be analysed and “a decision made on the next step.” (5)

As the standoff escalated, relations between China and Vietnam rapidly deteriorated. Anti-China riots broke out in Vietnam as protesters set fire to factories forcing thousands of Chinese to flee the country. A foreign policy meeting in June failed to reach any consensus, with Beijing refusing to back down, and Vietnam vowing to defend its territory. At one point, a Chinese ship damaged a Vietnamese fishing boat. Chinese crewmen then arrested six Vietnamese fishermen for allegedly fishing in Chinese waters. On the 2nd of July 2014, China’s National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) moved the oil rig back into Chinese territory. According to the company’s website, the rig discovered oil and gas, allowing China to complete its mission a month earlier than planned. The website hinted at future moves in the area saying that the data would be analysed and “a decision made on the next step.” (5)

Chinese Strategy

On the 7th of January 2015, Robert B. Kaplan, noted author on geopolitics, and senior fellow at the Centre for a New American Security, addressed a seminar at John Hopkins University where he presented “Chinese Views, Strategy and Geopolitics”.

Repeating the words of a founder of geopolitical thought, Halford MacKinder, from more than one hundred years ago, Kaplan said that China was geographically suited to be a great power in virtue of its 9000 kilometres of coast, its land mass, and its access to mineral resources in the western part of the country.

Kaplan says China bristles at the idea of the US Navy and Air Force in the Pacific, tolerating it because it has no choice. From China’s point of view, a U.S. naval/air force presence in the East China Sea from Japan and South Korea, south past Taiwan to the Philippines in the South China Sea, and through the Malacca Strait is a wall of containment preventing it from becoming a greater power.

According to Kaplan, public displays such as sending in oil rigs is all about status and territory. He maintains that China’s ambition is to achieve strategic parity with the United States without ever coming into conflict with it. “Naval power is not just about fighting. It’s about placing ships to influence diplomacy, to project economic power, to work naval deployments in coordination with diplomatic initiatives, with economic pressure, with intelligence operations, etc. to affect the thinking of American allies in the Asia-Pacific region”. (Kaplan, R.B., 2015)

Kaplan says China’s actions in the South China Sea are an effort to intimidate Vietnam and other countries in the region so it can control the Paracel and Spratly Islands within the so-called Nine-dash line encircling the islands. Another part of China’s strategy is to negotiate agreements with countries individually rather than with groups such as ASEAN. In some respects, maintains Kaplan, China’s strategy is similar to U.S. strategy in the Caribbean Basin 200 years ago.

Munroe Doctrine

In the early 19th century, the United States enacted the Monroe Doctrine, a foreign policy directive aimed at consolidating American influence by preventing European powers from further colonising the western hemisphere. Any country trying to interfere with states in North or South America would be viewed as acts of aggression. Though the 1823 doctrine also made it clear that it would not interfere with countries already in the area.

Washington’s reasons were straightforward. “The three main concepts of the doctrine – separate spheres of influence for the Americas and Europe, non-colonisation, and non-intervention – were designed to signify a clear break between the New World and the autocratic realm of Europe. (7) It was a question of conflicting visions based on mercantilism since both the U.S. and Europe wanted to increase influence and trading ties throughout the region.

Kaplan says the Greater Caribbean is the geopolitical centre of the western hemisphere, what he calls the American Mediterranean. Following the same logic, the South China Sea is the Asian Mediterranean, a place where “China sees goals and opportunities in the same way a younger U.S. saw opportunity in the Caribbean.” (Kaplan 2015). China is now at a point where it has consolidated its land mass, gone through the years of the Cultural Revolution, and later Tiananmen Square, developed its economy and is now in position to push beyond into the South China Sea.

So far, neither the presence of the U.S. Navy, nor international dispute resolution mechanisms have failed to prevent China from playing a greater role in the region.

Burma

If China is to secure its economic interests and energy dependency in the face of the Malacca Dilemma, and offset the containment of the U.S. navy in the Pacific, it has few other options than to increase its presence along the routes leading from oil sources in Africa and the Persian Gulf through the Malacca Strait. Another option would be to reduce its dependency on the Malacca Strait.

For years, reducing this dependency was a tall order given that there are no other sea routes between China’s oil sources in Africa and the Persian Gulf except the Malacca Strait.

However, over the years, China’s state-owned oil company, China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) has invested 2.5-billion dollars in a dual gas and oil pipeline from Manday Island in the Burmese port of Kyaukpyiu, across Burma, also known as Myanmar, to Kunming, the capital of China’s south-western province of Yunnan. The 2400-kilometre gas pipeline went into operation in 2013 carrying methane gas from offshore Burma. On the 29th of January 2015, the oil pipeline went into operation. “This oil pipeline runs parallel to the gas pipeline, directly transferring Beijing’s oil imports from West Asia and Africa. The gas and oil pipelines help solve China’s “Malacca Dilemma,” increasing its energy security tremendously.” (8) By bypassing the Malacca Strait, the pipeline “shortens the distance the oil will have to travel by sea to reach China by 1120 kilometres (700 miles). It also cuts by 30 per cent the time this liquid black gold will take to get to the Middle Kingdom.” (9) However, given the volume of oil needed to run China’s economy, and further industrialise the country, China is not about to abandon its efforts to ensure that the Malacca Strait remains open. “In an effort to moderate its strategy and avoid attracting attention, Beijing is relying more on economic initiatives to strengthen its ties with small but critical islands in the Indian Ocean.” (10)

However, over the years, China’s state-owned oil company, China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) has invested 2.5-billion dollars in a dual gas and oil pipeline from Manday Island in the Burmese port of Kyaukpyiu, across Burma, also known as Myanmar, to Kunming, the capital of China’s south-western province of Yunnan. The 2400-kilometre gas pipeline went into operation in 2013 carrying methane gas from offshore Burma. On the 29th of January 2015, the oil pipeline went into operation. “This oil pipeline runs parallel to the gas pipeline, directly transferring Beijing’s oil imports from West Asia and Africa. The gas and oil pipelines help solve China’s “Malacca Dilemma,” increasing its energy security tremendously.” (8) By bypassing the Malacca Strait, the pipeline “shortens the distance the oil will have to travel by sea to reach China by 1120 kilometres (700 miles). It also cuts by 30 per cent the time this liquid black gold will take to get to the Middle Kingdom.” (9) However, given the volume of oil needed to run China’s economy, and further industrialise the country, China is not about to abandon its efforts to ensure that the Malacca Strait remains open. “In an effort to moderate its strategy and avoid attracting attention, Beijing is relying more on economic initiatives to strengthen its ties with small but critical islands in the Indian Ocean.” (10)

Bay of Bengal

India controls the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal giving it a strategic position from which to monitor all shipping traffic heading to Indonesia, Malaysia and the Malacca strait. Burma administers Great Coco Island and Little Coco Island approximately 20 kilometres northeast of the Andaman Islands. There have been frequent reports since the 1990’s of China using the islands for intelligence and naval purposes, which has made India wary. A Chinese military presence in the Coco’s Islands would allow Beijing to monitor the activities of the Indian navy as well as of other powers in the region. It would also affect other regional powers such as Australia and the U.S. and strengthen China’s foothold in the India Ocean”. (11) Given growing Chinese investment in Burma, Beijing’s military presence in the area is highly probable.

Maritime Silk Road or String of Pearls?

In Beijing in February 2014, the Chinese and Sri Lankan foreign ministers Wang Yi and Gamini Lakshman respectively, announced plans to “fully expand maritime cooperation and jointly build the maritime silk road of the 21st century”. (13) In real terms, the Maritime Silk Road calls for China to work with partners in the East and South Asian region to develop maritime infrastructure, especially ports. The proposal was originally raised among ASEAN nations but China’s joint announcement with Sri Lanka and its investment in such ports as Kuantan, in Malaysia, Gwadar, in Pakistan, and Colombo, in Sri Lanka indicates Beijing’s wider reach.

Another name for China’s upgraded ports and maritime facilities from the South China Sea to the Arabian Sea is ‘string of pearls’, a phrase coined in the west that has military connotations. Beijing favours the term Maritime Silk Road, stressing that its motives are economic. The spokewoman for China’s Foreign Ministry, Hua Chunying, says China’s Maritime Silk Road is an “economic belt” aimed at “integrating all the existing cooperation, especially that in the field of connectivity with neighbouring and regional countries and enabling everyone to share development opportunities.” (14)

Another name for China’s upgraded ports and maritime facilities from the South China Sea to the Arabian Sea is ‘string of pearls’, a phrase coined in the west that has military connotations. Beijing favours the term Maritime Silk Road, stressing that its motives are economic. The spokewoman for China’s Foreign Ministry, Hua Chunying, says China’s Maritime Silk Road is an “economic belt” aimed at “integrating all the existing cooperation, especially that in the field of connectivity with neighbouring and regional countries and enabling everyone to share development opportunities.” (14)

China says it’s not building military bases, merely ensuring the security of Sea lines of Communication (SLOC). However, Beijing’s strategy to secure its economic and energy interests, while enhancing its influence throughout the Western Pacific, through the Malacca Strait to the vast area of the India Ocean basin raises more questions than answers. Despite its actions in the South China Sea, where do you draw the line? Should a line be drawn? If so, when? Neither the United States nor any of the countries claiming sovereignty over the Paracel and Spratly island chains knows the answer. While the world is in various stages of conflict over such resources as oil and gas (Russia, Ukraine, Europe), China continues to import oil and gas from the Persian Gulf, and oil operations off the coast of Africa, taking no part in local conflicts, which have a polarising effect on the rest of the planet. Syria, the Islamic State, Somalia, and Boco Harum come to mind. China comes across as low-key and subtle in its moves, for example, getting its message across with an oil rig instead of guns, then quickly withdrawing while quietly building a pipeline across Burma seemingly while the rest of the world is looking elsewhere. In trying to overcome what it sees as a dilemma that threatens its economic existence, Beijing plays its card close to the chest, and follows a multi-level strategy.

What’s next?

From its liar in the Middle Kingdom, the Chinese dragon has once again stretched its wings, and while appearing to ignore the rest of the world behind such containment structures as the U.S. Navy, and its regional allies, it has quietly overcome a dilemma that threatened its economic existence, while deftly managing to expand its influence from the Western Pacific to the Indian Ocean. Judging by American efforts to strengthen the Asia pivot by looking for more islands to set up military facilities, and India’s diplomatic efforts to shore up its zone of influence in the Indian Ocean, the west has taken notice, and wonders what the dragon will do next.

Bibliography

(1) Johnson, K. (2015, February 20). Reefer Madness: Why is China on a Building Spree in the South China Sea? Retrieved March 17, 2015, from

Reefer Madness: Why Is China on a Building Spree in the South China Sea?

(2) Zweig, D., & Jianhai, B. (2005, October 1). China’s Global Hunt for Energy. Retrieved March 19, 2015, from http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/61017/david-zweig-and-bi-jianhai/chinas-global-hunt-for-energy

(3) Wong, E., & Ansfield, J. (2014, June 16). Spratly Archipelago China Trying to Bolster Its Claim Plants Islands in Disputed Water. Retrieved March 18, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/17/world/asia/spratly-archipelago-china-trying-to-bolster-its-claims-plants-islands-in-disputed-waters.html?_r=0

(4) Wong, E., & Ansfield, J. (2014, June 16). Spratly Archipelago China Trying to Bolster Its Claim Plants Islands in Disputed Water. Retrieved March 18, 2015, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/17/world/asia/spratly-archipelago-china-trying-to-bolster-its-claims-plants-islands-in-disputed-waters.html?_r=0

(5) Hodal, K. (2014, July 17). Despite oil rig removal, China and Vietnam row still simmers. Retrieved March 18, 2015, from http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/17/oil-rig-china-vietnam-row-south-china-sea

(6) Kaplan, R.B, January 7, 2015, “Chinese views, Strategy and Geopolitics”, Seminar Series, John Hopkins University

(7) Milestones: 1801-1829, Monroe Doctrine 1823. (n.d.). Retrieved March 17, 2015, from https://history.state.gov/milestones/1801-1829/monroe

(8) Baruah, D. (2015, February 24). The Small Islands Holding the Key to the Indian Ocean. Retrieved March 18, 2015, from http://thediplomat.com/2015/02/the-small-islands-holding-the-key-to-the-indian-ocean/

(9) Meyer, E. (2015, February 9). With Oil and Gas Pipelines, China Takes a Shortcut Through Myanmar. Retrieved March 18, 2015, from http://www.forbes.com/sites/ericrmeyer/2015/02/09/oil-and-gas-china-takes-a-shortcut/

(10) Baruah, D. (2015, February 24). The Small Islands Holding the Key to the Indian Ocean. Retrieved March 18, 2015, from http://thediplomat.com/2015/02/the-small-islands-holding-the-key-to-the-indian-ocean/

(11) Ibid

(12) Tiezzi, S. (2014, February 13). The Maritime SIlk Road vs The String of Pearls. Retrieved January 5, 2015, from http://thediplomat.com/2014/02/the-maritime-silk-road-vs-the-string-of-pearls/